The jab - Nahida Abdulhamid

22 December 2021

Oriental practice, Islamic origin and patriarchy… all have displaced Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s contribution to immunisation by Nahida Abdulhamid, Policy Analyst at GGI.

The coronavirus pandemic has drawn the world’s attention to vaccination and the rapid pace of vaccine development. So now feels like a good moment to meet the pioneer of immunisation in England, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.

Lady Montagu and the origins of immunisation

Lady Mary was an English aristocrat, poet and writer. In 1712 she married Edward Wortley Montagu, who later served as the British ambassador to the Sublime Porte. She joined her husband for his Ottoman embassy, spending the next two years of her life in Constantinople (today known as Istanbul). There, she witnessed a practice which was unfamiliar to people in Britain at the time – inoculation.

Convinced of its safety and effectiveness, Lady Mary believed that this practice was the solution to smallpox – the deadliest disease of the 18th century, wiping out millions of people and disfiguring Lady Mary herself. Whilst in Turkey she had her son Edward inoculated, and on her return to England she arranged to have her daughter inoculated too, observed by three members of the Royal College of Physicians, including a physician to the King.

Lady Mary’s daughter was the first person to be protected in this way in the West, and she made good progress and lived to the age of 76. In later life, she became wife to the Prime Minister and mother of 11 children.

The broader introduction of inoculation into England included some terrible medical ethics with the technique tried on prisoners and orphans. Caroline, Princess of Wales (wife to the future King George II) was a more willing pioneer, having two of her children inoculated. This strengthened the argument that inoculation works and with all the publicity the practice began to spread.

Immunisation - an import from the East to the West

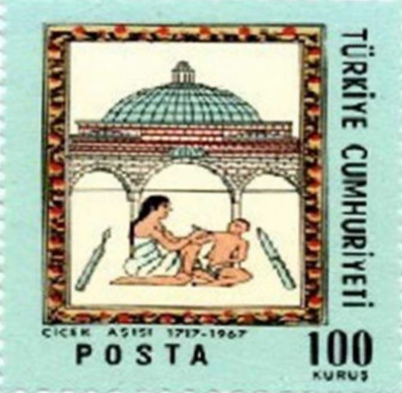

The historic origins of immunisation are often forgotten, although highlighting the contribution of Lady Mary, it is also important to remember the group of nameless women who carried out this practice in Constantinople. If it weren’t for them, exporting the process to the West would have not been possible. So, what was it that Lady Mary observed during her stay?

In Constantinople Lady Mary noticed that smallpox was harmless and women did not scar, they were able to keep their skin intact and beautiful. Lady Mary was so fascinated by this and wrote a letter to her friend in 1717, describing what she had seen (and, incidentally, providing the original source for the phrase ‘in a nutshell'):

“There is a set of old women, who make it their business to perform the operation, every autumn, in the month of September, when the great heat is abated… The old woman comes with a nutshell full of the matter of the best sort of smallpox, and asks what vein you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer her, with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch) and puts into the vein as much matter as can lie upon the head of her needle, and after that, binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell . . .”(1)

In other words, the method was to introduce the smallpox virus into an uninfected person, thereby providing immunity from the disease. Unfortunately, getting things off the ground in Britain was not easy.

Interestingly, there were ‘anti-vaxers’ in 18th century London too, condemning the practice as ‘Turkish’, and the Royal Family’s involvement as ‘German’. Lady Mary was herself often hooted at in public ‘as an unnatural mother who had risked the lives of her own children’(3). The English medical establishment disapproved of Lady Mary’s import for many reasons, ranging from sexism, racism and religion alongside medical scepticism. William Wagstaffe, a British physician, expressed his view very clearly, stating that inoculation is something practised by a:

“few ignorant women … amongst illiterate, and unthinking people ... the country from whence we deriv’d this experiment will have but very little influence on our faith.”(4)

Wagstaffe saw Lady Mary’s import as something ‘alien and inappropriate’. In this period, it was inconceivable to think of a woman changing the thinking of men.

It should come as no surprise, then, to see the physician and scientist Dr Edward Jenner receive all the fame for inoculation for his work some 70 years after Lady Mary’s actions.

Using similar methods and ideas as Lady Mary, Jenner realised that cowpox could be a substitute for the more dangerous smallpox. His procedure was taken up globally, receiving many awards and honours.

Despite the foundation Lady Mary set for Jenner’s experiment, historians and medical students over the years have only learnt about Dr Jenner. It is only now that the Royal College of Physicians of London is looking into ways to celebrate her contribution.

If we delve into this topic further, we find that the practice of inoculation not only starts at Constantinople but has been documented in places as far afield as China and Sudan.

Inoculation has, of course, inspired the development of vaccines for many more infectious diseases, turning the world into a much safer place. But its history has been presented in a way that displaces and silences pioneers such as Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. It’s time we put that right.

Footnotes

1. Letter from Lady Mary Wortley Montagu to Sarah Chiswell, written from Adrianople 1, April 1717. Edited by Lord Wharncliffe 1837

3. Grundy, Isobel; Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: Comet of the Enlightenment; Oxford University Press 1999

4. A Letter to Dr. Freind; shewing The Danger and Uncertainty of Inoculating the Small Pox London: Samuel Butler, 1722 pg. 4-6