Time for kindness

22 May 2020

This week (18-24 May) is Mental Health Awareness Week. This year’s theme is kindness – a particularly appropriate choice as we head towards our tenth week of lockdown and the effects of this unprecedented period of social isolation are felt ever-more keenly.

There’s widespread recognition of the impact the pandemic is having on mental health as societies all over the world wrestle with the challenges of isolation – challenges that include financial insecurity, health concerns and home schooling, among many others.

There are numerous elements of this multi-faceted challenge but a particularly tough one for people to come to terms with is a feeling of powerlessness. Apart from staying away from other people, what can those who aren’t essential workers do to feel useful in the fight against COVID-19?

One clear answer to that question is to be kind. It’s one of the big lessons of COVID-19, according to the respondents to a survey carried out in Northern Ireland by the Mental Health Foundation to mark Mental Health Awareness Week. More than two thirds of respondents (68%) said being kind to others had a positive mental effect – even more than the 64% who said the kindness of others had a positive effect on them.

Kindness in the NHS

One of the stories shared by the Mental Health Foundation to mark this week comes from Suba, a junior doctor in the NHS, who has been working in the emergency department of a London hospital throughout the crisis.

Suba’s story outlines some of the challenges associated with working as a junior doctor at such a difficult time for the NHS. She talks about the helplessness she feels when there’s nothing she can do to help patients, about the difficulty of constantly rotating between departments and not having enough time for her own loved ones, and about the challenge of managing end-of-life conversations with patients and their relatives.

All of these challenges take their toll – to the point where personal defences are seriously compromised. Suba says: “It feels like it would only take one more thing to push you over the edge, such as getting a ticket for parking in the wrong section of an empty staff car park, rushing to the canteen on a busy day to find it closed five minutes earlier, dealing with an angry patient/relative/colleague when your emotional reserve is empty...”

Suba expected her job to be difficult in these extraordinary times. What she didn’t expect was what she calls the ‘immeasurable acts of kindness and gratitude’ she has experienced. Acts such as local people sewing scrubs for NHS staff, car park companies allowing NHS staff to park for free, or the weekly applause from her neighbours.

Suba says these acts ‘keep her afloat’. But should we rely on such spontaneous acts of kindness or should the concept of kindness be enshrined in policy – or even legislation?

The Mental Health Foundation’s chief executive, Mark Rowland, certainly believes so. He says: “To have a major impact on improving our mental health, we need to take kindness seriously as a society. In particular, we need to make kindness an important part of public policy.”

Kiwi kindness

New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern has earned global praise for the way her government has tackled COVID-19. New Zealand went into an early and complete lockdown on 25 March when there were only 102 cases in the country. By 19 May, there had been just 21 deaths. As a response it was swift and decisive – there was nothing soft or easy about it. But the difficult message was always delivered with kindness and empathy. In fact, Ardern’s recurring message throughout the crisis has been consistent: ‘Be strong. Be kind.’

This combination of kindness and strength should come as no surprise. Ardern has long campaigned for kindness and collectivism over isolationism and protectionism. She has embedded these principles into her country’s long-term economic strategy so that one of the key measures of any policy is the impact it will have on the quality of people’s lives.

Until COVID-19 came along to upset the economic applecart, it was a successful policy too – New Zealand’s economic performance has been steady under her leadership and the country’s first well-being budget, published in May last year, set out numerous measures that had been taken to improve mental health, support for children, helping the Maori community and many other priority areas.

Lessons for NHS boards

Crises such as COVID-19 inevitably compromise the well-being of staff and – as Suba the junior doctor rightly points out – the reality is that you cannot pour from an empty jug.

What should NHS boards take away from all of this? To treat well-being as a priority rather than a nice-to-have. To discuss tangible and measurable ways they might improve the well-being of their staff. And to enshrine those measures in policy so that they are not forgotten when the world returns to some sort of normality.

Lessons for individuals

Of course, it is important that employers and legislators keep kindness and well-being at the forefront of their approach but this is also an area where everyone has a personal role to play. We must be kind to ourselves. At a time of great stress and uncertainty, that is not always easy.

One way to handle this self-care is to compartmentalise the way we allow circumstances to affect us. It is possible to be or feel well even when circumstances around us are not well at all. What is personal to us is what we choose to connect to – family, work, community etc. – but being kind to ourselves means choosing to isolate ourselves from the elements of our lives that are out of our control.

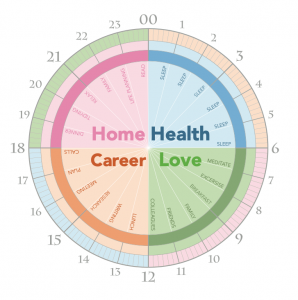

The most certain way of being kind to ourselves and to others is to respect time. Equilibrium can best be achieved by seeking to balance our priorities in life. Those priorities might be as follows:

- Health – What we do to maintain our physical health and well-being, from diet to lifestyle and exercise.

- Home – How we manage our surroundings, a particularly important element in lockdown, when we are forced to spend more time than we would perhaps choose to in our homes.

- Career – Those activities we do to give ourselves a sense of purpose. For many, this will be a job, but it could also be volunteering, or perhaps doing something creative.

- Love – How we interact with those we care most deeply about, whether that’s a partner, parents, children or close friends.

Balancing these four elements might not be easy to begin with but taking stock of each area and recording for ourselves how well balanced we feel they are is a good start. Then we can decide what we might do to strike a better balance between them and start working towards that.

As ever, we are keen to hear your views. If this briefing prompts any questions or comments, please call us on 07732 681120 or email advice@good-governance.org.uk.

Martin Thomas

Copywriter