18 February - Non-executive directors - with Sir Michael Marmot

21 February 2022

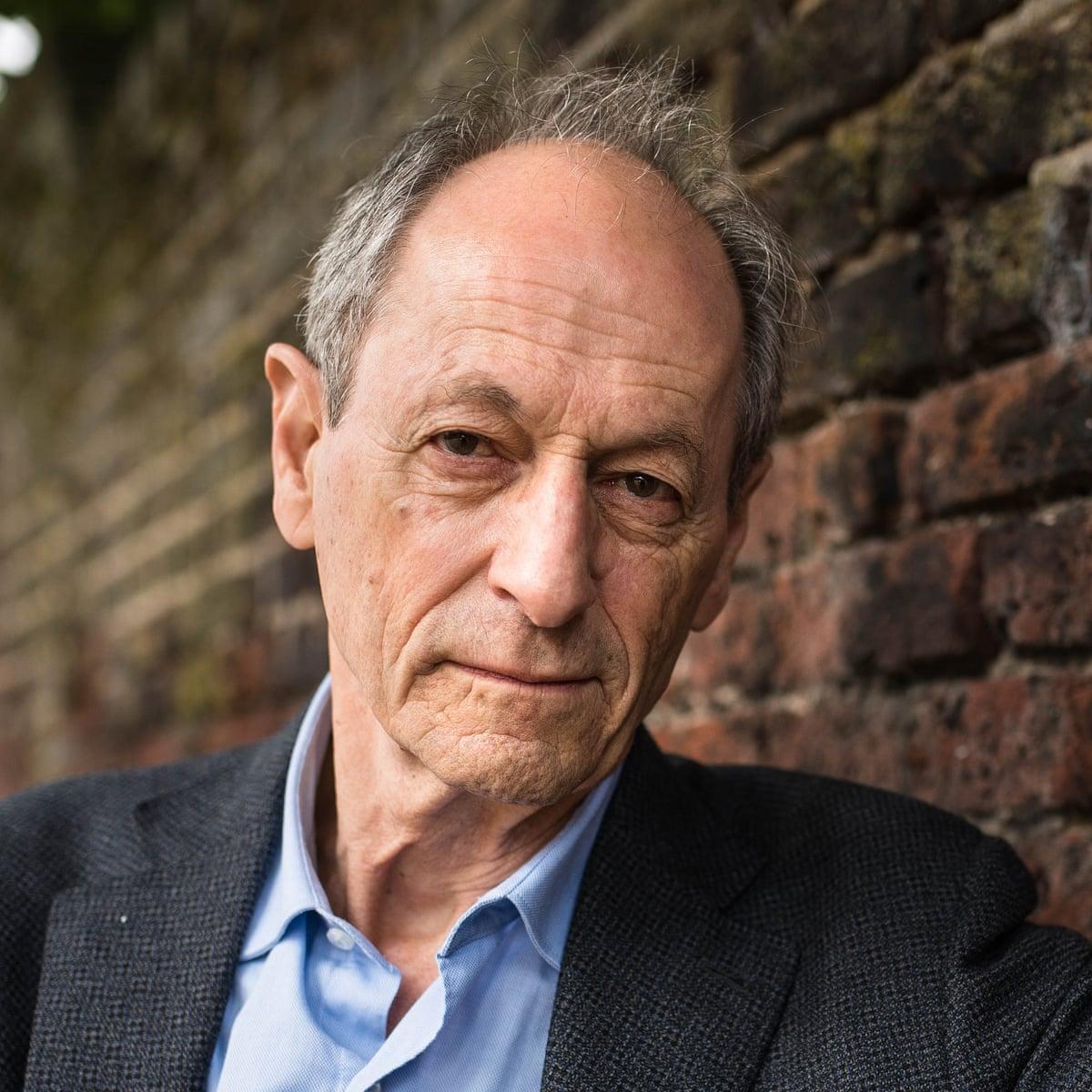

Our special guest for the non-executive directors webinar on 18 February was Sir Michael Marmot, recipient of the 2021 Good Governance Award, former president of the World Medical Association, and author of several landmark reports on health inequalities.

Introducing the session, GGI CEO Andrew Corbett Nolan said: “An important aspect of integrated care is levelling out health inequalities as part of population health management. We’ve published a lot on this subject, including our 2018 report with IBM Watson. The triple aim of better care, improved outcomes and lower cost doesn’t really work in the NHS unless you also add in two further aims: the wellbeing of health and social care providers and reducing health inequalities. That’s part of our mission here at GGI.”

Sir Michael was in conversation with GGI special adviser Usman Khan. Here are some of the highlights.

Sir Michael Marmot: “In February 2020 we produced Health Equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. We looked back and discovered that we had lost a decade, life expectancy stopped improving after having improved by about one year every four years.

“In 2010 there was a dramatic change: health inequalities increased. And the greater the deprivation of an area, the poorer life expectancy became. Health for the poorest 10% outside London was getting worse. That was pre-pandemic. If you thought in government that the age of austerity was necessary, it’s not true. No other rich country did what we did, and we had the most dramatic slowdown in life expectancy of any country apart from the US. We took political choices that damaged the health of the population and increased inequalities.

[…]

“I called the Covid-19 review Build back fairer because I said we don’t want to go back to the status quo. Where we were in February 2020 was far from ideal. Health for the poorest people was actually getting worse and inequalities were increasing. What the pandemic did was to reveal the underlying inequalities in society and amplified them. For example, the 2020 drop in life expectancy was 0.9 years for women and 1.2 years for men in England. In the north west region the drop was about 1.2 years for women and 1.6 years for men. Wow! Other countries had negligible drops in life expectancy during the pandemic and very little excess mortality; ours was enormous. We managed the pandemic very poorly and it had the impact of increasing inequalities. The government, quite rightly, congratulated themselves on vaccine but important though that was, it didn’t address underlying inequalities in health.”

[…]

“I asked myself: why did we have the slowest improvement in life expectancy of any rich country apart from US pre-pandemic and the highest mortality in the pandemic. What’s the link? Now I’m speculating but I think the link works at four levels:

- Poor governance and political culture

- Increasing social and economic inequalities

- Disinvestment from public services – we were ill equipped

- We weren’t very healthy, which increases Covid risk

[…]

“It’s garbage to say we were just following the science. You can’t follow the science. Scientists are always uncertain. Any scientist who says they know the truth is exaggerating, to put it kindly. You look at evidence and then you have to make a political/social judgement. The science doesn’t tell you to lock down. Models can make predictions but they’re hugely uncertain and then you need judgement – and our judgement was sorely lacking. We had the worst of both worlds.”

[…]

“Political culture in this country took a steep turn downwards around the time of the Brexit referendum, when we stopped discussing important things. In 2010, no one was concerned about Europe – it was on no one’s agenda. We were concerned about jobs, the NHS, the economy, the climate, inequalities and our children. Then we made it the biggest single issue. We damaged the country economically, in terms of international relations, in terms of our position on world stage, and we damaged our politics.

“There’s a very important political debate to be had about where on the spectrum from the individual to the collective we should take action to improve public health. At one end of the debate people will privilege individual rights and freedoms and will say seatbelts, fluoride and so on are an intolerable erosion of individual freedoms. And people at the collective end of the debate will say ‘no, we need social action for the public good’. That’s an entirely legitimate debate to be having. I’m entirely respectful of people who would push either individual responsibility or collective responsibility. That’s a good debate to be having – the right debate to be having.”

[…]

“You get insights from strange places. I got one from the living room of a Nobel prize-winning economist in Princeton, New Jersey. I drew him two graphs, both showing mortality by level of deprivation. One showed higher mortality across the board but a shallow social gradient. The second showed improvement in mortality but the richer you were, the greater the improvement. He said to me: ‘All economists would go for the second one. Everybody’s health is better’. I said: ‘But it’s more unequal – it’s less fair’. And he said ‘So what? Everybody’s health is better, surely you wouldn’t want a situation that was more equal, but everybody was worse off?’

“And I wouldn’t want that. But how about drawing more lines on the page? I want a situation where everyone’s health is better and it’s more equal.

“Saying ‘build back better’ doesn’t really get at the equity question. I chose the title ‘build back fairer’ as a deliberate echo of build back better but wanted to put equity and fairness front and centre. It’s not enough to say ‘overall we’re doing better’, the question is, are we doing fairer?

[…]

“My experience of speaking to senior people in local government is that you can’t tell which party people are from, they just care about improving conditions for people who live and work in their patch. I’m naïve, I know, but I think politics at local government level matter less.

“Who are the key players locally? We’re setting up a network in the next month, funded by Legal & General, a big financial organisation who wanted to work with me. Key players locally are local government, the voluntary sector, businesses and ICSs. We’re working with ICSs in east London, the south east, Cheshire & Merseyside, Greater Manchester and elsewhere… We elaborated five principles when I was president of BMA: education and training, seeing the patient in broader perspective, anchor institution – good employer, impact on local community etc, working in partnership, and advocacy for better policies and change. That’s all to do with addressing the social determinants of health – quite apart from the core business of treating the sick and providing social care. Of course that must also happen in an equitable way. We’re working with ICSs to encourage them to be involved in those five areas.”

[…]

“We showed [in 2020] that spending per person in local government was cut in the decade after 2010 and the steepness of cuts grew with the level of deprivation in the area. So for the least deprived 20%, the cut in spending per person was 16%, and the more deprived the area the greater the reduction – in the most deprived 20% the cut was 32% per person. The government was making cuts to deprived areas that were steeper than those they were making in less deprived areas.

“In the north of the country those local government cuts amounted to something like £430 per person over the decade; in the 2021 allocation of levelling up funds the north was being given £33 per person.

“So, they had an active policy of making the poor poorer and taking money away from deprived areas.”

[Responding to a question about how to address health inequalities this without the necessary funding]

“That’s where advocacy comes in; it’s blatantly unfair. Fairness is at the heart of all my arguments. […] Local action can’t let central government off the hook. When East Germany was incorporated into FDR, Germany spent two trillion euros over 25 years, which is about £70bn a year. In levelling up white paper it points to £4.8bn for 2021-24, which is £1.2bn a year. The money really matters.”

[Responding to a question about the role of primary care]

“I have nothing to criticise [about primary care], they’ve been the heroes and heroines of the pandemic. The criticism that’s been piled on them is appalling. They’re short-staffed and under huge pressure.

“That said, primary care is at the front line. There’s a movement for social prescribing – which is very much about working in partnership, about saying ‘this individual in front of me has problem x but to solve that takes more than a pill, it involves dealing with the problems of homelessness, domestic violence, lack of employment and the like. As a GP I can’t do it on my own, but I have local connections that could help make it happen.’

[…]

“Resources, of course, are vital. We have national politics that aren’t delivering on either side. That’s a real failure. I’d like a proper right/left political discussion – but a real one. We’ve got something totally other now, with neither side paying attention. That’s the negative reason why we need to get positive action locally. I’d like better national politics – a more grown-up conversation. We’ve been riveted by party-gate – I want to talk about child poverty!

“We should all have as our over-riding concern health equity, the fair distribution of health for the populations we serve. That should be our number one priority.

“Crudely speaking, there are two ways to achieve this in ICSs: to make sure there’s equity in access to high quality treatment, and to take the right steps to prevent people getting sick which means action on the social determinants of health.”

These meetings are by invitation and are open to all NHS non-executives directors, chairs and associate non-executive directors of NHS providers. Others may attend by special invitation.

If you have any comments, questions or suggestions about these webinars, please contact: events@good-governance.org.uk